return statement and exception handling problem

Because return serves two purposes: ending the method run and returning a value. We don't typically put return in the exception handling structure, but at the end of the method.

[Example] Correct handling of return and exception structures

def test01():

print("step1")

try:

x = 3/0

# return "a"

except:

print("step2")

print("Exception: 0 cannot divide")

#return "b"

finally:

print("step4")

#return "d"

print("step5")

return "e"#In general, do not put return statements in try, except, else, finally blocks, and some unexpected errors will occur. Suggestions at the end of the method.

print(test01())

Execution results:

step1 step2 Exception: 0 cannot divide step4 step5 e

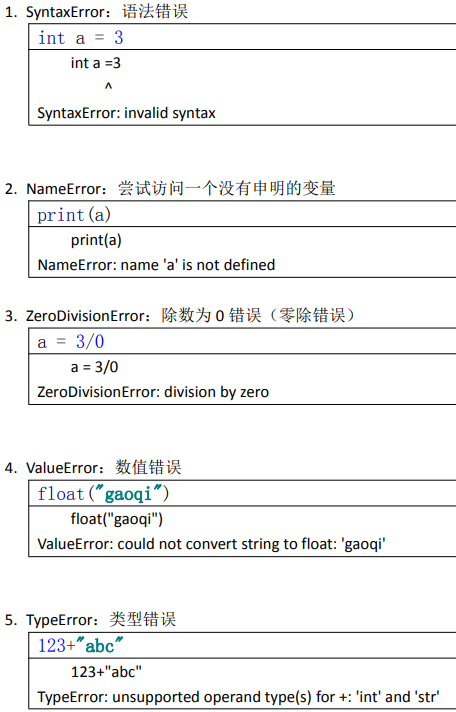

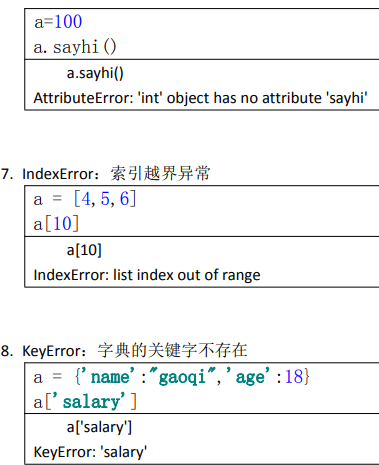

Resolution of common anomalies

Exceptions in Python are derived from the BaseException class. In this section, we test and list some common exceptions

6. AttributeError: Access properties that do not exist for the object

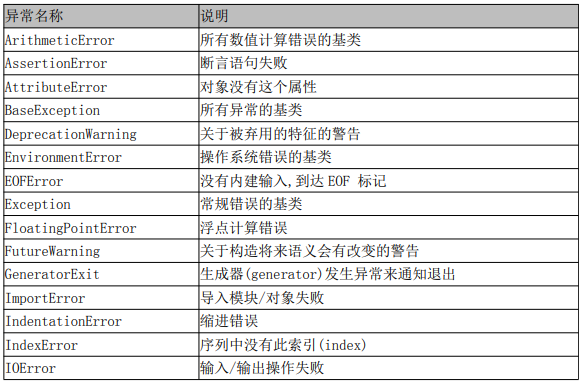

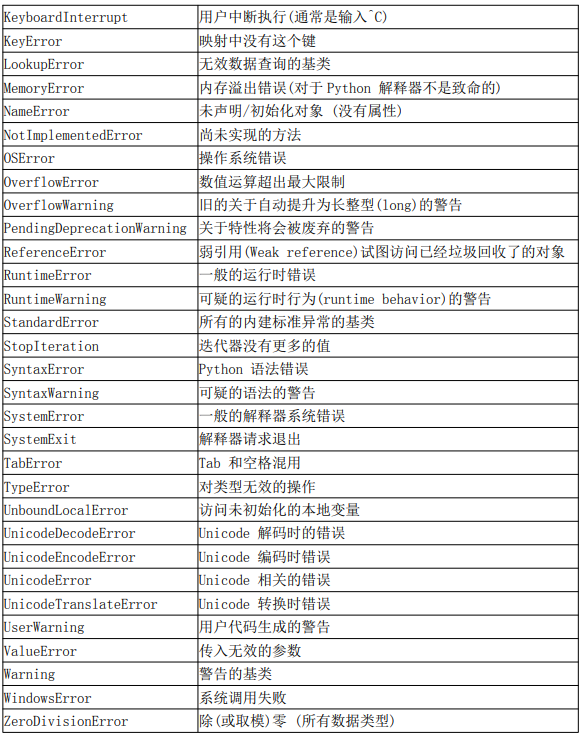

Summary of common anomalies

with Context Management

finally blocks execute because of exceptions or not, and we usually release code that releases resources. In fact, we can use the context management of with to more easily release resources.

The syntax structure of with context management is as follows:

with context_expr [ as var]:

Statement block

With context management, resources are automatically managed and the field or context before entering the with code is automatically restored after the execution of the with code block. Jumping out of the with block for any reason, whether or not there is an exception, will always guarantee the normal release of resources. It greatly simplifies the work and is very common in situations related to file operation and network communication.

[Example] with context management file operations

with open("d:/bb.txt") as f:

for line in f:

print(line)

trackback module

[Example] Print exception messages using the Traceback module

import traceback

try:

print("step1")

num = 1/0

except:

traceback.print_exc()

Execution results: (print error information in detail)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:\Users\89444\PycharmProjects\pythonProject\class9_07.py", line 4, in <module>

num = 1/0

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

step1

Process finished with exit code 0

[Example] Use traceback to write exception information to the log

#coding=utf-8

import traceback

try:

print("step1")

num = 1/0

except:

with open("d:/a.txt","a") as f:

traceback.print_exc(file=f) #Error Printing to New Folder

Custom exception class

In program development, sometimes we need to define exception classes by ourselves. Custom exception classes are usually run-time exceptions, usually inheriting Exception or its subclasses. Naming is usually suffixed with Error and Exception.

Custom exceptions are thrown actively by raise statements.

[Example] Custom exception classes and raise statements

#Test custom exception classes

class AgeError(Exception): #Inherit Exception

def __init__(self,errorInfo):

Exception.__init__(self)

self.errorInfo = errorInfo

def __str__(self):

return str(self.errorInfo)+",Error in age! Should be at 1-150 Between"

############Test Code################

if __name__ == "__main__": #If True, the module runs as a stand-alone file and the test code can be executed

age = int(input("Enter an age:"))

if age<1 or age>150:

raise AgeError(age)

else:

print("Normal age:",age)

Execution results: (wrong age entered)

Enter an age:544

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:\Users\89444\PycharmProjects\pythonProject\class9_08.py", line 12, in <module>

raise AgeError(age)

__main__.AgeError: 544,Error in age! Should be at 1-150 Between

Process finished with exit code 1